The Railroad Commission's Role in Protecting Property Owners

“Conservatives are persuaded that private property and freedom are closely linked.” Kirk’s seventh principle of conservatism will not find many objections among conservatives. Private property ownership—and with it restrictions against unfair property taxes, abusive uses of eminent domain, policies of redistribution, and attacks on inheritances—is a bulwark of free government. When the government limits the right to private property, it limits the individual’s and the community’s right of self-determination.

“Conservatives are persuaded that private property and freedom are closely linked.” Kirk’s seventh principle of conservatism will not find many objections among conservatives. Private property ownership—and with it restrictions against unfair property taxes, abusive uses of eminent domain, policies of redistribution, and attacks on inheritances—is a bulwark of free government. When the government limits the right to private property, it limits the individual’s and the community’s right of self-determination.

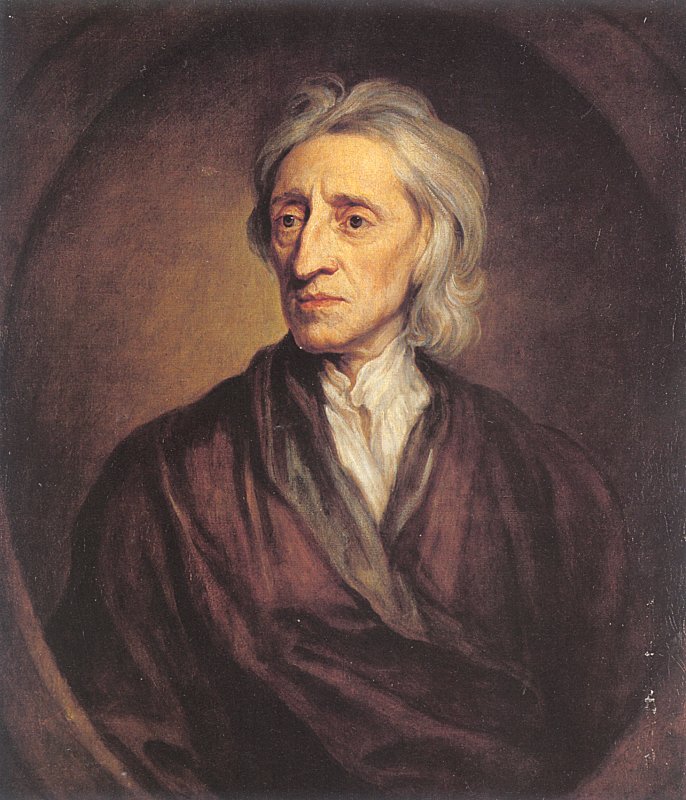

To derive a justification and defense of property, I rely on a Lockean, and thus Madisonian, definition of private property. This definition may alienate some libertarian readers as it provides a sound defense of intellectual property rights by building through a property of conscience.

In Chapter 5 of the Second Treatise, Locke gives his seminal account of property rights. It runs as thus: Man alone is in possession of himself and through his drive and ingenuity extends his dominion beyond himself. Man is in possession of himself because no other individual gave him his will, conscience, or abilities; thus, no one else can exert dominion over him, except that to which he consents for, he owes nothing but to himself. Man, then, takes possession of property when it lay in common and he mixes his labor with it. Simply put, if there is unowned property available, and I take it out of its natural state by mixing my labor with it, that property becomes mine so long as there is enough left over for others to sustain themselves for I have no right to deprive someone else of providing for themselves. An acorn becomes mine if it is laying on the ground or on the tree and I take it out of its natural state by mixing my labor with it, ie. plucking it from the tree or picking it up from the ground. The mixing of labor makes it mine because that acorn is no longer what it had been--my labor made it something which it had not previously been through the virtue of my efforts--which means no body else can stake a claim to it without depriving me of the fruits (or nuts in this case) of my labor.

The Lockean argument gets a bit more complicated, but in terms of how common property becomes private, this is it in Lockean terms. This is why Locke and his intellectual heirs consider private property paramount for the preservation of liberty for there is no real distinction between man and his property, for property is nothing more than an extension and physical manifestation of a man's liberty.

Madison has a more expansive, and sometimes confusing, articulation of property rights but he understands it as Locke does. Madison uses property to describe what man possesses within himself, ie what Locke would call will or labor, and those external objects that becomes man's possessions through mixing himself with it, ie land, hogs, etc. This formulation is articulated by Madison in a 1792 essay entitled "Property". Madison writes, "In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights. Where an excess of power prevails, property of no sort is duly respected. No man is safe in his opinions, his person, his faculties, or his possessions. Where there is an excess of liberty, the effect is the same, tho' from an opposite cause. Government is instituted to protect property of every sort; as well that which lies in the various rights of individuals, as that which the term particularly expresses. This being the end of government, that alone is a just government, which impartially secures to every man, whatever is his own." We may conclude that protecting property, broadly understood, is the sole object of government for both Madison and Locke.

Building from the philosophical justification of property rights, it is easy to develop a legal and practical defense. In my book, The Price of Politics, I trace the legal and historical roots of property rights through contemporary eminent domain decisions in order to provide a critique of legal attacks on property through Supreme Court decisions such as Kelo v. City of New London.

Also important is the consequentialist defense of property rights. Property rights engender people to their community by giving them a vested interest in seeing that community thrive. Property rights also bestow upon people a pride of ownership in which they seek to develop their property in the most fruitful manner possible. Property ownership serves as the foundation for an invested, engaged and active citizenry. For these reasons, and perhaps others that could not be fit into this space, we should look suspiciously at proposals of unitization.

Unitization, or pooling, is a scenario in which, most commonly, an oil or gas exploration company needs to purchase a large area in which there are several land owners over different tracts and some are unwilling to sell. Unitization says that if a minimum threshold his met, say 70%, then all the landowners must sell. This deprives property owners of their rights. It gives the right of one property owner dominion over the property of another. Moreover, the use of eminent domain--or a related principle such as unitization--to seize private property for use by a private company is unconscionable.

In the upcoming Railroad Commissioner primary, we should be especially attune to these developments in Texas and ask the candidates where they stand on these issues for unitization could become something the Commission could have to address. Malachi Boyuls has stated his opposition to this issue and made it a centerpiece of his campaign. For the candidates who have not raised the issue, or clearly articulated their opposition, we must press them on where they stand and also why they don't think property rights are an important enough issue to make the centerpiece of their campaign.

Comments

Join the discussion on Facebook

Join the discussion on Facebook.