Explainer: Options for Evacuated Afghans

Authored by Danilo Zak and orginally published on immigrationforum.com.

Authored by Danilo Zak and orginally published on immigrationforum.com.

In the aftermath of the U.S. troop withdrawal and the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban in August 2021, 85,266 vulnerable Afghans were evacuated on flights out of airports in Kabul and Mazar-e-Sharif. The evacuees were first flown to third countries for extensive vetting and screening. Then, in the fall of 2021, more than 76,000 of the evacuees were transferred into the U.S., initially brought to military bases for additional medical screening and processing and then resettled into communities across the country. A few thousand more remain in third country “lily pad” locations, but are set to be brought to the U.S. soon.

These evacuees generally would have been eligible for either refugee and/ or Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) status, but those processes were too slow and backlogged to work effectively in the context of an emergency evacuation. Instead, more than 70,000 (over 94%) of those resettled in the U.S. thus far have been processed under humanitarian parole.

Parole offers only limited, temporary benefits and — unlike refugees and SIVs — no clear path to permanent status. These evacuees meet the legal definition of a refugee, but because they came under parole they are forced to live in legal limbo, uncertain about their options or their future in this country.

This explainer compares the various pathways currently available for Afghan evacuees to stay in the U.S. and discusses why adjustment legislation remains necessary and urgent.

What are the options for evacuated Afghans to stay in the U.S.?

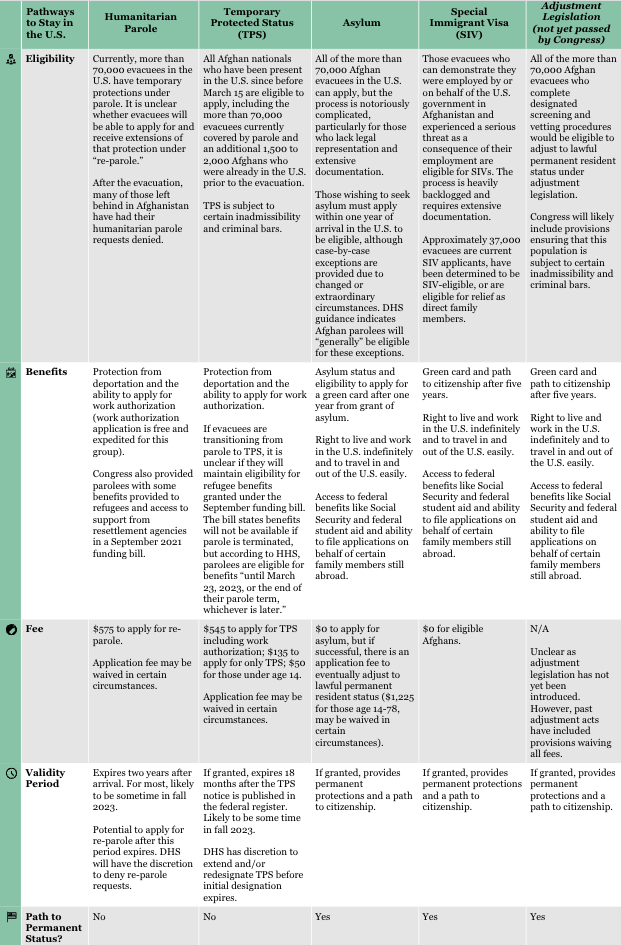

Afghan parolees do have some options to stay in the U.S. beyond their initial two-year grant of parole, including applying for re-parole, initiating an asylum claim, continuing an SIV application, and transitioning to Temporary Protected Status (TPS). Some evacuated Afghan children may also be eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile status. Each of these pathways come with significant challenges and roadblocks, and many advocates and experts have called for the passage of adjustment legislation& to create a clear, simplified path to permanence for evacuees.

The following chart compares the various pathways currently available for Afghan evacuees.

Why aren’t Afghan evacuees eligible for refugee status?

Refugee status is – in general — reserved for those seeking permanent protection from outside the U.S. While virtually all Afghan parolees would otherwise meet the eligibility criteria for refugee status (under either Priority 1 or Priority 2), they are already present in the U.S. and the U.S. refugee admissions program (USRAP) is unavailable to them. Usually, those in the U.S. who meet the definition of a refugee are directed to instead seek protection through the asylum system or to apply for other status.

There have been some limited exceptions to the rule that those seeking protection must be located outside the U.S. Under federal law, there is no categorical or statutory bar to completing refugee status processing from within the U.S. The last such instance was in 1999 under the Clinton administration, when 20,000 Kosovars fleeing the Milošević regime were airlifted to the U.S. and completed their refugee processing after arrival.

However, even if USRAP were available to Afghan evacuees, it would be a suboptimal option. Like the asylum and SIV processes, the refugee process is under-resourced, uncoordinated, and slow-moving. Adding more individuals would threaten to only further delay protections for others around the world who are stuck in the pipeline, and the sluggishness of the process — which can often take more than two years from start to finish — is a key reason parole was used during the evacuation in the first place.

Why do we need adjustment legislation if TPS, asylum, and SIV status are available?

TPS provides no path to permanent status, and the asylum and SIV pathways provide no guarantees. TPS — while an important protection for some – is largely redundant for those with parole, providing similar temporary protections and benefits, while lacking a path to permanent status. The asylum and SIV processes do come with a path to permanent status, but they are both heavily backlogged, resource intensive, and could result in complications for pro se applicants and/or those who were forced to destroy or leave behind documentation while escaping Afghanistan.

Adjustment legislation would provide an easier, more streamlined path to permanent status that includes robust screening and vetting procedures and mitigates harm to others who are stuck in backlogs across the system.

I. Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

TPS for Afghanistan – announced on March 16 but not yet officially noticed in the Federal Register — was an important step to protect those present in the U.S. before the evacuation, but provides only limited additional protections and benefits to the more than 70,000 evacuees who are already here under humanitarian parole. Like parole, TPS provides temporary protection from deportation and work authorization. Like parole, TPS protections are limited to less than two years and set to expire sometime in the fall of 2023. And just like parole, TPS provides no path to permanent status.

There are some differences between TPS and parole. Historically, most TPS recipients have been able to extend their temporary status as the grant itself is repeatedly extended and/or redesignated by the administration (although this is not assured, as the Trump administration attempted to terminate several long-standing TPS grants). The process for applying for and receiving re-parole to extend parole protections is far less clear. Re-parole applications could cost up to $575 per person and might result in a higher denial rate – leaving Afghans with no protections at all.

Even if available, both re-parole and repeated TPS grants indefinitely leave Afghan evacuees in temporary status, a problem that is all too common in the U.S. immigration system. Evacuees would not be able to fully integrate into their communities, left to wonder if the next 18-month stint would be their last. In addition, for those favoring extensive vetting of Afghan evacuees, indefinite TPS is inferior to adjustment legislation, as TPS grants and renewals do not require significant additional screening or in-person interviews.

II. Asylum

In the absence of adjustment legislation, the asylum system likely provides the best chance for many evacuees to eventually receive a green card and a path to citizenship in the U.S. However, there are several concerns associated with requiring 70,000+ Afghan parolees to file asylum applications for a chance at stability.

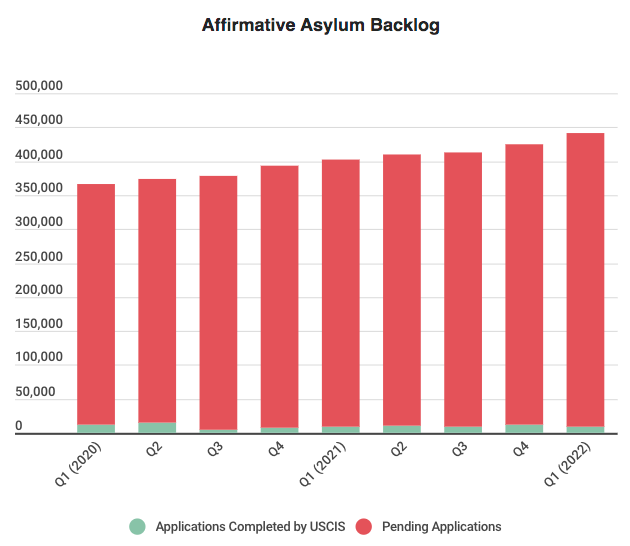

To start, the asylum backlog at USCIS (also known as the “affirmative” asylum backlog) currently sits at over 432,000 cases and growing. In the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2022, over 17,000 more asylum applications were filed than were completed. Even though USCIS employs a last in, first out (LIFO) policy for processing asylum applications, Afghan evacuee claims will still likely take months — if not years – to complete.

Even before making it through the backlog, the application process itself is extremely resource intensive and difficult to navigate without legal representation. Asylum seekers are 3.1 times more likely to receive asylum grants when they have a lawyer, and pro se applicants are routinely denied for failing to file properly or because they misunderstand convoluted eligibility requirements and precedent. Despite efforts to coordinate pro bono support, most evacuees lack access to a lawyer to assist with an asylum claim. And even with representation, each individual application can take months to prepare and requires extensive documentation to succeed – documentation which an applicant may have had to destroy or leave behind while fleeing across Taliban checkpoints. In some instances, the U.S. embassy in Kabul itself destroyed applicants’ documents to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Taliban.

Another factor to consider is the impact of tens of thousands of additional asylum claims on the rest of the immigration system. Other asylum applicants, including some who have been waiting for decades, would be forced deeper into the backlog. Adjudication duties would fall to a limited number of asylum officers, who will be increasingly deployed to lead new border management processes.

Source: USCIS

III. Special Immigrant Visas (SIV)

Of all the pathways discussed in this explainer, SIVs have the most restrictive eligibility requirements. Many evacuees who faced threats due to their support of the 20-year U.S. mission in Afghanistan are ineligible for SIV status because they were not directly employed by or on behalf of the U.S. For example, members of the Afghan Female Tactical Platoon — who directly supported U.S. efforts but were employed by the Afghan National Army — are ineligible for SIVs. Many extended family members of principal SIV applicants who were evacuated are nonetheless ineligible for SIV protections themselves. Others who worked for U.S.-based non-governmental organizations or who were otherwise particularly vulnerable are also ineligible.

The approximately 37,000 evacuees who are eligible for an SIV may not be able to complete the process due to strict documentation requirements. Even though the Taliban has gone door-to-door targeting those with ties to the U.S., SIV applicants must still prove they have faced a particular threat in Afghanistan due to their employment. Applicants must also obtain both a letter of employment verification from the relevant H.R. department and a positive letter of recommendation from a direct supervisor (who must be a U.S. citizen). As with asylum claims, some of the necessary documentation may have been destroyed or left behind during the evacuation.

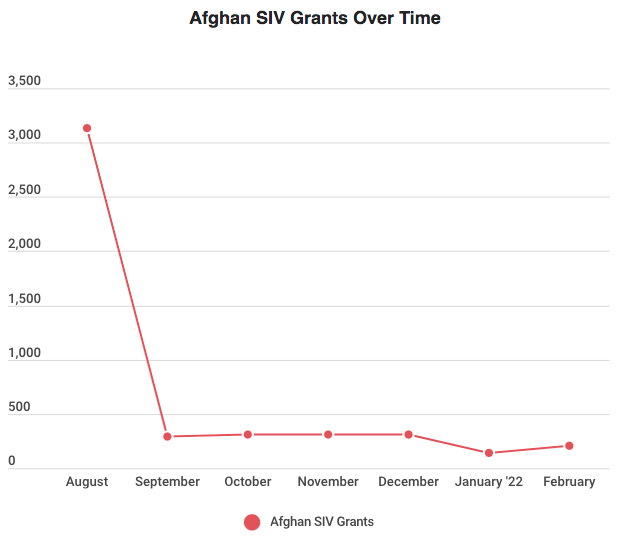

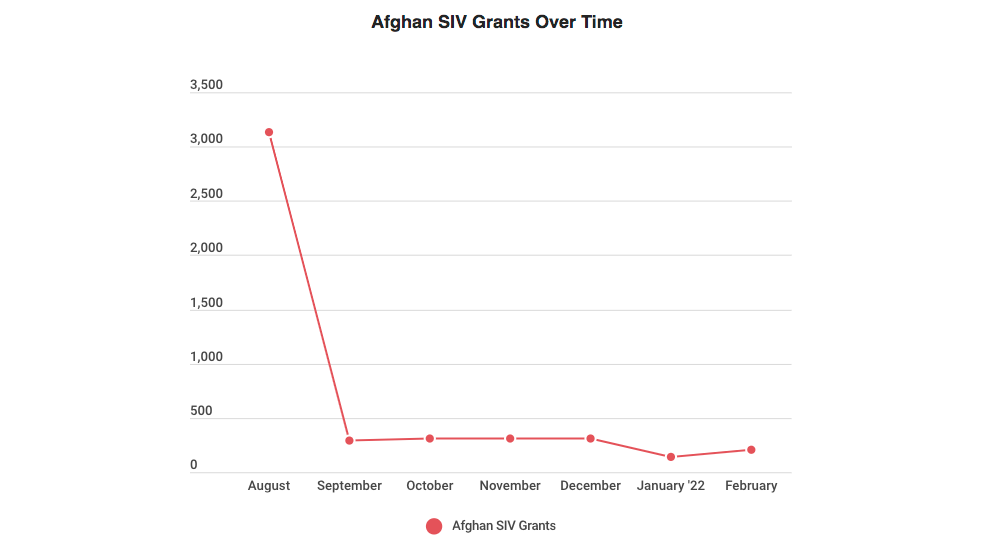

To make matters worse, the SIV process is also extremely backlogged and slow-moving. SIV grants are supposed to be completed within 9 months of an application, yet the process often takes more than three years. Reported numbers of SIV grants have declined significantly since summer 2021, despite the tens of thousands who remain in the backlog both in the U.S. and who were left behind in Afghanistan. Adjustment legislation would provide easier access to permanent status for SIV-eligible evacuees, and allow the government to prioritize cases of those who remain in danger.

Source: Refugee Processing Center

Will applying for asylum or TPS impact an evacuee’s future ability to access other pathways?

No, initiating an asylum claim or an application for TPS will not negatively impact evacuees who later seek lawful permanent residence under future adjustment legislation. Applications for TPS will also not impact future asylum claims (as long as the claim occurs within the one-year filing deadline or the applicant is eligible for an exception), and those with pending asylum claims can still apply for TPS.

However, as noted above, asylum claims are lengthy, intensive, and — regardless of how compelling a case is — very difficult to file without legal representation. TPS applications, while less complicated, also require extensive paperwork and evidence and come with a fee. While applying for available protections carries no risk of losing out on a future adjustment act, all applications should still be considered carefully and, preferably, with the assistance of counsel.