Legal Migration Can Control the Border

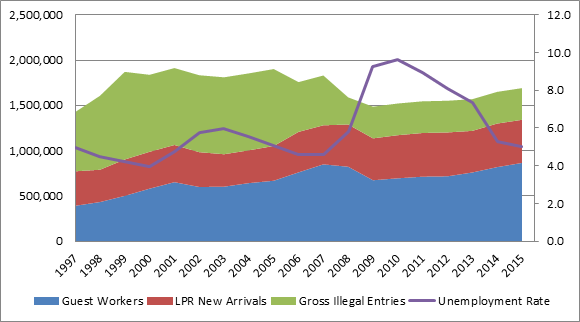

I recently wrote a piece about the increase in guest workers and the remarkably consistent level of entries, legal and illegal, of workers and new lawful permanent residents. The main choice the U.S. government faces is whether the migrants who come here are legal or unlawful. Excluded from my previous blog were J-1 visas for researchers, au pairs, and the like.

About a third of unauthorized immigrants worked in service jobs in 2012, as well as 28 percent of foreign-born residents who are not naturalized, compared to just 16.7 percent of natives. Au pairs and child care are an important component of these economic sectors so including them is important to understand the shift from unlawful to lawful immigration (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Guest Worker Visas Issued, Green Cards for New Arrivals, and Gross Illegal Immigrant Inflows

Sources: State Department, Department of Homeland Security, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Pew.

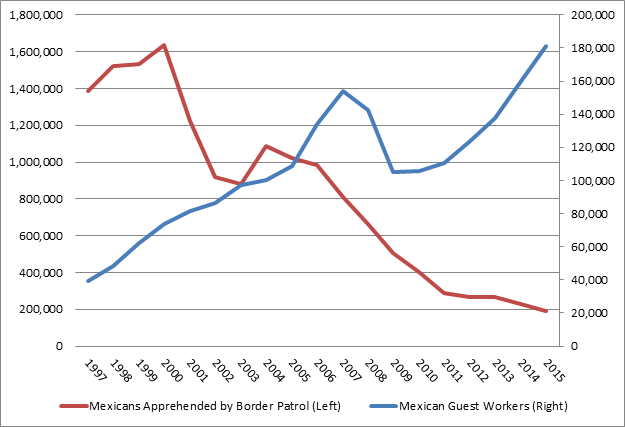

The biggest decline in unlawful immigration has come from Mexico but the surge in Mexican J-1s by itself cannot possibly explain that. In 1997, 3,633 Mexicans were issued J-1 visas while only 9,044 were issued the same visa in 2015. Regardless, the change in the number of Mexican apprehensions since 1997 explains virtually all of the change in the total number of apprehensions with a correlation coefficient of 0.994. The inclusion of J-1s does not change the conclusion from my previous post.

Rising wages in Mexican states that sent migrants to the United States, lackluster U.S. economic growth, and increased border security all played a role in shrinking Mexican unauthorized immigration. The increase in border patrol from 1997 to 2015 is closely correlated with the number of new guest worker visas issued to Mexicans and the unemployment rate. The numbers of Mexicans apprehended is negatively correlated with all three—with the number of border patrol agents coming in on top at -0.95, Mexican guest workers at -0.78, and the U.S. unemployment rate at -0.68. The adjusted R-squared for all the variables is 0.86.

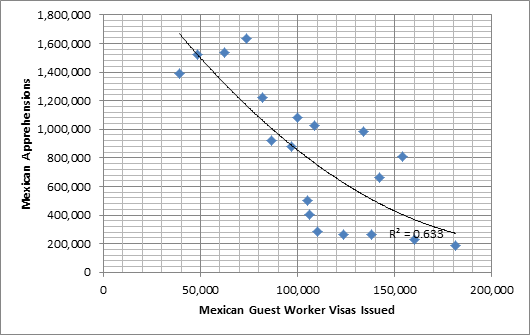

There is an impressive trade-off between the number of Mexican guest workers and apprehensions of them attempting to enter unlawfully (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the same figures in a more dramatic, less technical graph. Increasing the number of guest workers for Mexicans is also much cheaper than hiring new border patrol agents.

Figure 2: Guest Worker Visas for Mexicans and Mexican Apprehensions

Sources: State Department and Department of Homeland Security.

Figure 3: Guest Worker Visas for Mexicans and Mexican Apprehensions

Sources: State Department and Department of Homeland Security.

The number of guest worker visas issued to Hondurans, Salvadorans, and Guatemalans has flattened since 2005 while the number of apprehensions of them at the border has more than doubled. Expanding the number of guest worker visas and making more of them available to Central Americans would be a cheap, effective, and economically beneficial way to diminish the flow of unlawful immigrants from those countries and to expand control over the border.

Guest worker programs do not have to replace every would-be unlawful entrant with a legal work visa. Each visa issued during the Bracero program of the 1950s and 1960s replaced about 3.4 Mexican unauthorized immigrants, on average. Legal migrant workers are preferred by American employers, the migrants themselves, and should be favored by policy makers too.