Three- and Ten-Year Bars Immigration Policy Brief

This immigration policy discourages undocumented immigrants from adjusting their status; because they face the risk of seeing their families separated, more immigrants have chosen to remain undocumented in the U.S. long term

Authored and originally published by fwd.us

Individuals who remain in the U.S. without authorization can be subject to immigration bars, like the three- and ten-year bars, which prevent them from re-entering the U.S. through a legal channel for up to 10 years

This is the situation facing millions of mixed-status families across the U.S. These immigration bars make it impossible for long-term undocumented immigrants, many of them spouses and parents of U.S. citizens, to “get in line” to receive a valid visa. Since the immigration bars were created, the number of undocumented immigrants remaining permanently in the U.S. has grown substantially.

By revising the immigration bars, including reforming the three- and ten-year bars and providing for more discretion in individual cases, Congress could allow immigrants with deep ties to the U.S. to access legal pathways and help keep American families together.

Immigration bars prevent immigrants who voluntarily leave the U.S. from returning legally for many years—sometimes permanently

These bars on re-entry, commonly referred to as the “three- and ten-year bars” or the “unlawful presence bars,” are punishments applied to undocumented immigrants who remain in the United States without authorization. Whether they entered unlawfully or overstayed a visa, individuals who remain unauthorized in the U.S. for more than six consecutive months are considered to be “unlawfully present.”

If they then leave the United States, even voluntarily, the bars are applied to prohibit them from re-entering through a legal channel for some years.1 The duration of the bar on re-entry depends on how long they were unlawfully present in the U.S.—less than a year is a three-year bar, and anything longer is a ten-year bar. If they have entered the U.S. without authorization multiple times, even as children, they may be subject to permanent bars.2 There are also additional bars for other immigration violations, like using false documents or making false statements. The bars separate families and bar integral members of our communities for years.

The immigration bars are a relatively recent policy, created as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) signed into law by President Bill Clinton. However, migration trends and the makeup of families and communities living in the United States have changed significantly since they were implemented, warranting renewed consideration of their effectiveness.

After immigration bars were created, more undocumented immigrants remained permanently in the U.S.

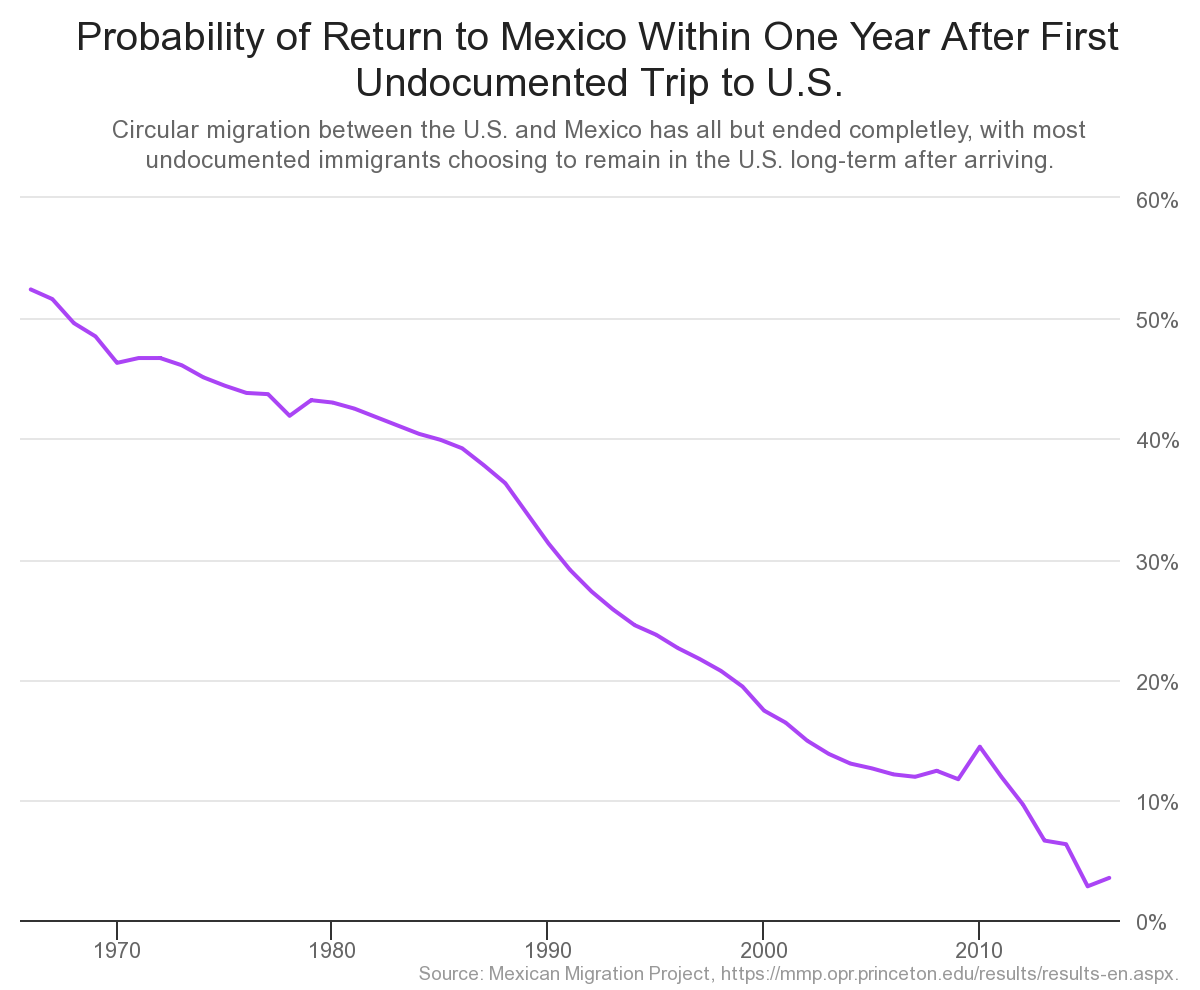

While the bars on re-entry were intended to punish unauthorized immigration, they have had unintended consequences, as undocumented immigrants have increasingly chosen to remain in the U.S. permanently, boosting the growth rate of the undocumented population.

Until relatively recently, immigration across the southern border was mostly circular, as immigrants (with and without authorization) traveled back and forth, often for economic opportunities, much more frequently. However, that changed when Congress started passing legislation to increase immigration enforcement and restrict legal channels.

For example, researchers found that increased enforcement policies implemented in the 1980s and ’90s did not discourage undocumented immigrants from Mexico from coming to the U.S. in the first place, but did make it far less likely that they would depart the U.S. after arriving. The likelihood of undocumented immigrants from Mexico returning home after being in the U.S. began to decrease after Congress boosted enforcement in 1986, and then decreased more significantly after IIRIRA imposed even more penalties and restrictions, including the bars on re-entry.

According to Douglas Massey, a Princeton professor who led this study, approximately 5.3 million people who were undocumented would have likely chosen to leave the U.S. if not for these increased enforcement measures. Since IIRIRA went into effect, however, the size of the undocumented population in the U.S. has grown significantly, with most undocumented immigrants remaining here for a long time.

In 1990, the number of undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. was estimated to be about 3.5 million; by 2000, that number had grown to 8.6 million, and has settled around 10 to 11 million in recent years. Roughly 68% of undocumented immigrants currently in the U.S. have lived here for more than 10 years, according to FWD.us estimates.

Reforming the 3- and 10-year bars would allow millions of U.S. citizens to sponsor their family members for legal status

Passing legislation to reform the three- and ten-year bars, and to allow immigration officers and judges to exercise discretion in cases involving U.S. citizen spouses and American families would allow millions of undocumented immigrants who otherwise qualify for a legal immigration pathway, like being sponsored by a relative or an employer, to apply for an immigration status and become legal permanent residents.

Reforming the bars would most directly benefit U.S. citizens hoping to sponsor their immediate family members, like spouses and parents, who are undocumented. For many, immigration bars are the main obstacle preventing them from securing certainty and relief for their families in the U.S.

For example, FWD.us estimates that approximately 1.1 million undocumented immigrants have a spouse who is a U.S. citizen who could sponsor them for a green card.3 On average, these individuals have lived in the U.S. for 16 years and have been married to their U.S. citizen spouse for at least a decade; we estimate that as many as 100,000 are DACA recipients. They would still have to formally apply with the government, pass background and security checks, and in most cases, they would have to leave the U.S. and re-enter under a new, legal status.

Pathways to legal status and citizenship benefit all Americans

Allowing undocumented residents an opportunity to secure legal status and pursue citizenship is generally good policy that benefits all Americans. It is a common-sense solution that provides relief and opportunity to millions of families, while also helping increase access to legal status for individuals who are undocumented. And it is clearly better than the alternatives, like continuing to bar otherwise-eligible immigrants from adjusting status, or attempting to forcibly deport millions of people from American communities.

After becoming citizens and being able to access lawful employment, undocumented immigrants would be able to significantly increase their economic contributions. FWD.us analysis shows that currently undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens would contribute an additional $16 billion annually to the U.S. economy, along with an additional $5 billion in federal, payroll, state, and local taxes. With lawful work authorization, previously undocumented immigrants could fill critical job openings, helping ease inflationary pressures caused by labor shortages.

Congress should reform the immigration bars and expand access to legal pathways

Reforming the immigration bars and allowing for discretion in cases involving U.S. citizens and American families is a narrow but meaningful starting point for bipartisan immigration reform, long supported by a host of policy experts, advocates, and lawmakers from both parties. As Congress has failed to achieve consensus on broad, bipartisan immigration reform, this is a targeted, common-sense policy correction that can help millions of American families.

Notes

- The law provides exceptions to the bars in limited circumstances, including for minor children, bona fide asylum applicants, battered women and children, and victims of trafficking. Certain immediate relatives of U.S. citizens can apply for waivers, including provision waivers that can be granted before the individual leaves the U.S.; however, the waivers require a very high standard of evidence, and many individuals who are granted waivers and believe they will be allowed to return end up being denied on other grounds.

- Individuals who have been unlawfully present for more than a year in aggregate can also be subject to a permanent bar on re-entry if they depart and subsequently attempt to re-enter without authorization, under INA 212(a)(9)(C)(i)(I). These bars can be appealed, but only after the individual has remained outside of the U.S. for at least 10 years. Individuals who departed or were removed and re-entered without authorization multiple times, but who have since remained in the U.S., may face this permanent bar if they attempt to depart and re-enter legally.

- Additionally, we estimate as many as 700,000 additional undocumented individuals who are parents of adult U.S. citizen children 21 years or older could also be sponsored for green cards if not prevented by the bars, though data limitations make it more difficult to accurately estimate the size of this population. All estimates are based on 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) data. See our Methodology for more details.