God Bless Fred Yaggi - Hero of the Munich Mission

This article from Norman Adams and Andy Adams originally appeared in ADAMS INSURANCE - THE ROUND UP.

"Customer" is really not the right word to describe Fred Yaggi. The Yaggi family has been so much more to Adams Insurance for the 40 plus years Norman and our team has been hunting and keeping up with Fred's activities and businesses (Fyco Tool & Die). To honor Fred's passing this week after a long and full life, we would like to republish a journal article first published in 1992.

The original article was written by Captain Martin Mayer, a B-17 pilot in the European theater. Mayer wrote the article as a remembrance and thanks to the man he credits with saving his life and the lives of every man aboard his B-17 on October 4, 1944. His name was Fred Yaggi.

Writing in 1992, many years after saying goodbye to Fred, Captain Mayer remembered Fred as "John Yoggi." Captain Mayer mistakenly substituted "John" for Fred's first name, but he correctly remembered him as "Yoggi" because that's what all the men called Fred during the war. At some point, Fred simply got tired of trying to correct them and went along with "Yoggi." For clarity's sake, we have corrected Captain Mayer's recollection here and the reader should rest assured that it has been confirmed after the article was published that this was indeed our Fred Yaggi.

MISSION MUNICH by Martin Mayer [originally published in 1992 Spring Issue of FRIENDS JOURNAL]

I write of this unforgettable day, those many years ago, primarily as a tribute to Fred Yaggi, the most loyal and gutsy friend I had ever met during my four years as a pilot in the Army Air Force.

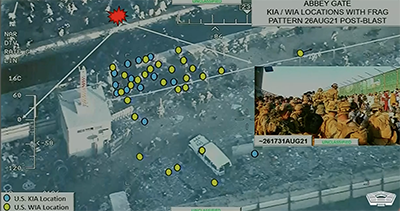

B-17s of the 414th Bomb Squadron coming off the target, the RR marshaling yards at Munich, on 4 October 1944-the mission described here. The flak that caused the incident is in clear evidence. (Photo: Mayer)

It has been nearly 47 years since I last saw Tech. Sgt. Fred Yaggi. We shook hands, wished each other luck, and said goodbye one day late in October, 1944. Yaggi had been my flight engineer/top turret gunner for 46 of my 50 missions while assigned to the 414th Squadron, 97th Bomb Group (B-l7s) based near Foggia, Italy. I have thought about him frequently during the intervening years, always with regret that I had not let him know adequately how deeply I felt about what he had done for me. It was an act of courage; but it was more than that. It was an act that said he was willing to quite possibly sacrifice his life to help me. That's the kind of thing you never forget.

The events of Wednesday, October 4, 1944, commenced sharply at 4:30am, when, having been awake for at least half an hour, I heard the operations orderly not far away waking up other crew members. When he reached my tent, he stuck his head inside and said, "Morning, Captain. Briefing at 5:15." I was "A" Flight leader and I was feeling the familiar "fifty mission jitters" because this was the last one - number 50. The jitters started, almost ritually, with the 45th. With each one thereafter, the feeling became a little more intense, particularly just before briefing. On this morning it occurred to me suddenly that my left wing man would be on his 48th.

After giving myself a cold water shave by candlelight, I commenced the somewhat elaborate procedure I had developed to keep my feet warm.

I first wrapped them in toilet tissue, followed by rayon socks. Over this went long wool socks, then ankle high, fleece-lined shoes. Just before climbing into the cockpit, I put on the GI flying boots, also fleece-lined. It was a bit cumbersome, but it worked great without losing too much of the sense of feel for the rudder pedals.

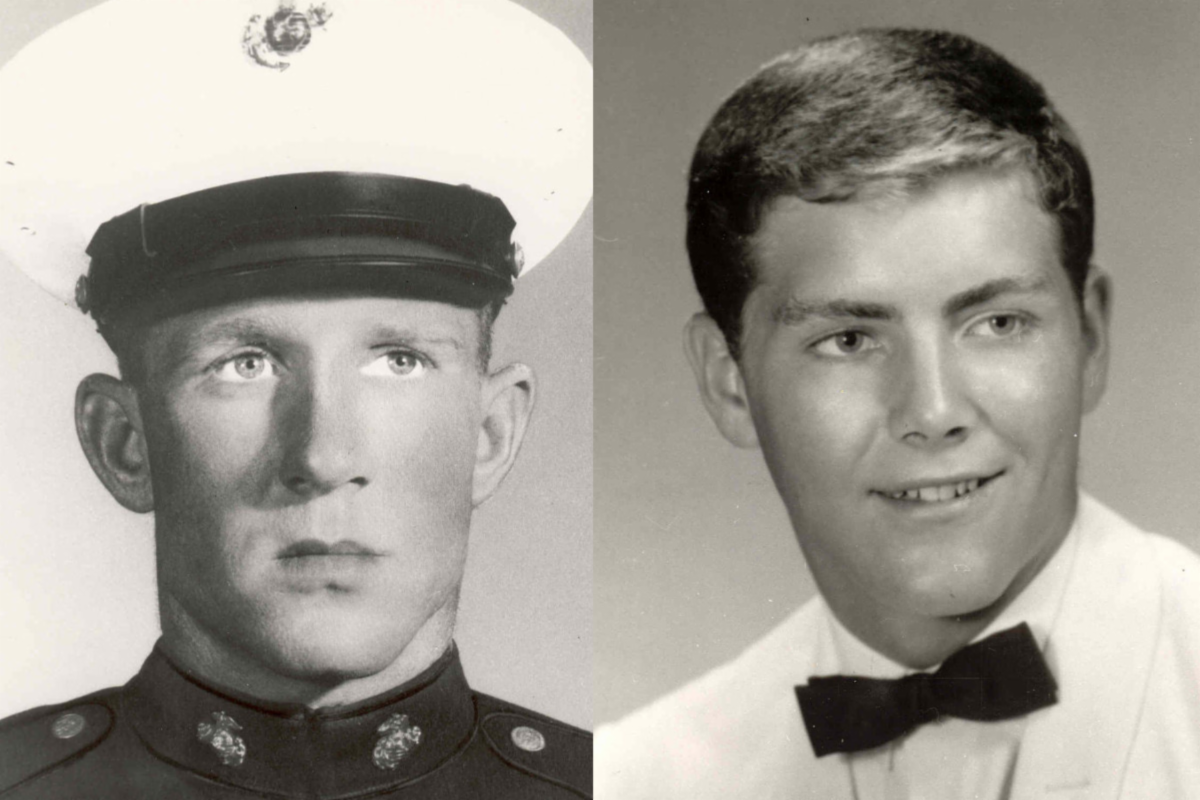

Lt. Martin Mayer, third from right, back row, and TSgt Fred Yaggi, first from right, front row, (Photo: Mayer)

At 5:15 am, better than 400 men were gathered in the large briefing room at group headquarters, most of us staring anxiously at the large cloth covered map of Europe. This was the time when everyone--but especially me on this crucial day--would hope for a "milk run." When the briefing officer appeared on the raised plat form, all chatter ceased as though cut off by a switch. It was as though all four hundred of us were holding our breath for the few seconds before the briefing officer pulled the cloth away. When he did, with a kind of flourish, what we were looking at was definitely not a milk run. The yellow string ran from Foggia all the way to Munich. The room filled with groans and all I could say was one four-letter word. Yaggi, sitting to my left, didn't say a word. Of all the targets we went after, the worst ones were Ploesti or almost any city in Germany. I had been to Munich before and It had seemed as though every 88mm antiaircraft gun in the German army was there--plus fighter attacks. Unlike earlier mis sions, however, we were now at least getting some P-51 and P-38 fighter cover.

As we approached the outskirts of Munich, flak became intense, as expected. One burst off my left wing tip was so close that I saw the red flash and heard the shell explode above the roar of four engines but, miraculously, no serious damage. If my left wing man had been where he should have been he would have been hit, and I'm sure destroyed. Later the ground crew counted some 50 holes in wings and fuselage, and left aileron cable severed.

Just before we reached the IP, Yaggi's guns let loose with a long burst at a fighter I couldn't see, and the cockpit filled with the familiar smell of cordite. Just as he stopped firing, Yaggi yelled into the intercom, "Navigator, 1 o'clock low!" Instantly, an Me 109 flashed into view directly in front of us, heading away, diving and trailing smoke. Since the navigator failed to fire and the ball turret gunner saw the fighter on fire and the pilot bail out, Yaggi was given credit for the kill. He had been tracking this fighter as it circled, getting into position to attack. When he did, it was from the rear, probably aiming for my number four man, the tail-end Charlie position and always a favorite target for Luftwaffe fighters.

Finally came the turn at the IP on a heading for the RR marshalling yards. Moments later I watched as the group lead opened his bomb bay doors and simultaneously came the welcome words in my headset from the bombadier, "Bomb bay doors open," then "Bombs away!"--the most welcome words of all. Every pilot in the group would be saying, as I was, "Now let's get the hell out of here!" But for me, the most critical part of the mission lay ahead, just a few minutes away. Since there were still 109s in the area, I was concerned about the other three planes in my flight holding a tight formation. I was particularly anxious about my right wing man, who kept dropping back, and on the radio I was continually urging, "Close it up! Close it up!"

While I was looking to my right, the words that I can still hear came in my headset. I recognized Yaggi's voice. All he said was, "Captain, look out!" I snapped my head around to the left. It was instantly apparent that my left wing man was about to collide with us. There was only one way to avoid a disastrous collision, and that I did it instinctively was testimony to my training. Strangely, as I look back on it, I felt no panic.

To prevent a collision the plane had to drop. If I had shoved the nose down the tail would have come up and no doubt been sliced off. If I had turned away from him in a tum to the right, the left wing would have come up and would also have been sliced off. If I had pulled up in a climb there was the danger of over-reacting, resulting in a power stall.

To make the plane drop I immediately chopped all four throttles all the way back to the stops. At the same time, I made a very slight nose-down tum toward him. This got my left wing out of his way and, hopefully, with all power off, there'd be enough clearance for the rest of the plane. Seconds later he slid directly over the top of us. Later, heading back to base and now completely alone, Yaggi came down from the turret and told me he could have reached up and touched the plane as it moved over us. I grabbed Yaggi's hand and said,"Thanks, Yaggi, best call you ever made!"

Capt Martin Mayer in October, 1944, after completing 50 Missions. (Photo: Mayer)

For a brief moment I was angry that my left wing man had very nearly destroyed two B-l7s and twenty crew members. But Yaggi quickly calmed me down when he suggested the logical explanation: that the plane had taken some flak, the pilot and/or co-pilot been killed or wounded, and the plane was out of control. After I had recovered to our original altitude I learned from other crew members that the last the plane had been seen It was still flying straight and level.

It was a happy crew that landed back at the base at Foggia early in the afternoon. We had been in the air for eight hours. Most of the crew had been unaware how close we had come to being scattered all over the German countryside until Yaggi told them what had happened.

Much later in the afternoon, the electrifying word flashed around the squadron that my missing wing man had landed! The plane had returned, flying alone, as I had done, but with one major exception. Most of the crew was missing. They had bailed out, it seems, very nearly over the center of Munich. I would not get the full story of what happened aboard that plane until 45 years later.

I flashback now to shortly after 4:30 am of this memorable day. I had finished my foot wrapping routine and was just about to leave my tent when I heard a cough from someone outside. I stepped out and to my surprise there was Yaggi. I said, "Yaggi, what are you doing here? You've finished your missions. You ought to be back in your tent in the sack.

Yaggi had completed his mission requirement nearly two weeks ahead of me and the rest of the crew. He had done this by flying as a fill-in crew member on days we were not sched uled to fly. Some days he had flown in the top turret position and others as a waist gunner. These were volunteer missions for fellows who had been grounded by the flight surgeon and--I found out later--he had flown for fellows who were just plain scared, making an excuse for them that they were sick. Not only that, but when he could have been heading for home, he had instead arranged with a friend in operations to hold up his Stateside orders until the rest of the crew and I had finished our missions. It was a fateful decision.

Now here he was outside my tent, and in response to my question he said, "One of the fellows in my tent works in group intelligence. He just came back from the briefing room. He told me where the mission's going today. You won't like it. It's Munich. My heart sank, feeling as though it was headed all the way down to my well wrapped feet. Yaggi continued, "I figured you'd need an experienced man in the top turret. The guy they've scheduled for you--I just don't think he's good enough. I'd like permission to fly with you.

Permission to fly with me! He was volunteering for a dangerous mission. He knew what Munich was like; we'd been there. I was deeply touched and I was glad it was dark.

I've never had any doubt that Fred Yaggi's courageous act put him in position to save my life and those of my crew. I hope that somehow, wherever he is, he will see this and get in touch. I'd like to grab his hand once again and this time, instead of "Good bye," I'd say, "Yaggi, you're one helluva guy."

Epilogue

It was not until September, 1989, at a reunion of the 97th Bomb Group in Clearwater Beach, Fla., that I finally got a first-hand account of what had happened aboard that plane flying off my left wing on Oct. 4, 1944. Several of us were standing in the lobby of the hotel trading war reminiscences. I had just finished telling in abbreviated detail about Fred Yaggi and our experience and then asked, "Did anybody ever hear what happened to that pilot who bailed out over Munich?" A fellow I had not known said, "Yeah, I can tell you. I was the radio operator on that plane." I doubt I have ever felt greater astonishment than at this wholly welcome coincidence.

This is what he told me: The plane had taken some flak damage as Yaggi had surmised. The co-pilot thought it was severe enough that he left his seat and went to the rear of the plane to check on it. While he was gone, the cockpit suddenly began to fill with smoke from a fire which had started under the flight deck, visible to both the navigator and bombardier. The pilot believed that when you're in combat you never try to second guess a fire--you either get out or plan to come down in pieces. [Author's note: After discovery of the fire, I believe the pilot's subsequent actions were ex actly correct. In particular, putting the plane on autopilot enabled the crew to get out easily. It was virtually impossible to get out of a B-17 or B-24 in a dive or a spin.]

Choking from smoke in his oxygen mask, he hit the bail-out alarm switch, put the plane on autopilot, grabbed his chute, and went out the lower hatch, following the navigator and bombardier. Three other crew members, including the light waist gunner named Paul Cook, went out through the bomb bay. Cook jumped with his GI 45 automatic firmly strapped around his waist.

It was during a brief period when there was no pilot in the cockpit that the plane had very nearly collided with my ship. It had been slightly out of trim, causing it to slide off to the right. When the co-pilot returned to the flight deck the fire had gone out, smoke had cleared and since all four engines were running smoothly, he quickly slid into the left seat. Then, with the flight engineer flying co-pilot, they lit out, hell-bent for home, praying there were no fighters around. It was one lonesome B-17 because, by now, my plane and the rest of the group were long out of sight.

The six crew members came down near Munich and spent the rest of the war in a prison camp--all except one. Paul Cook was shot by a German patrol shortly after he landed. Crew members knew him as an aggressive, gung-ho type, itching for a fight. They figured he'd gotten into a fire fight and, badly outnumbered, had gone down doing what he had very much wanted to do--fight Germans.

What an incredible story. Fred's son-in-law, Joe Slovacek, reports that eventually Fred and Captain Mayers had a reunion. Over two dozen family members came to thank Fred for their lives. Each one presented him with a personal thank you card. Captain Mayer made good on his promise and treated Fred like a true hero. We join him and say a prayer of thanksgiving for the life of Fred Yaggi.